Customer Services

Copyright © 2025 Desertcart Holdings Limited

Desert Online General Trading LLC

Dubai, United Arab Emirates

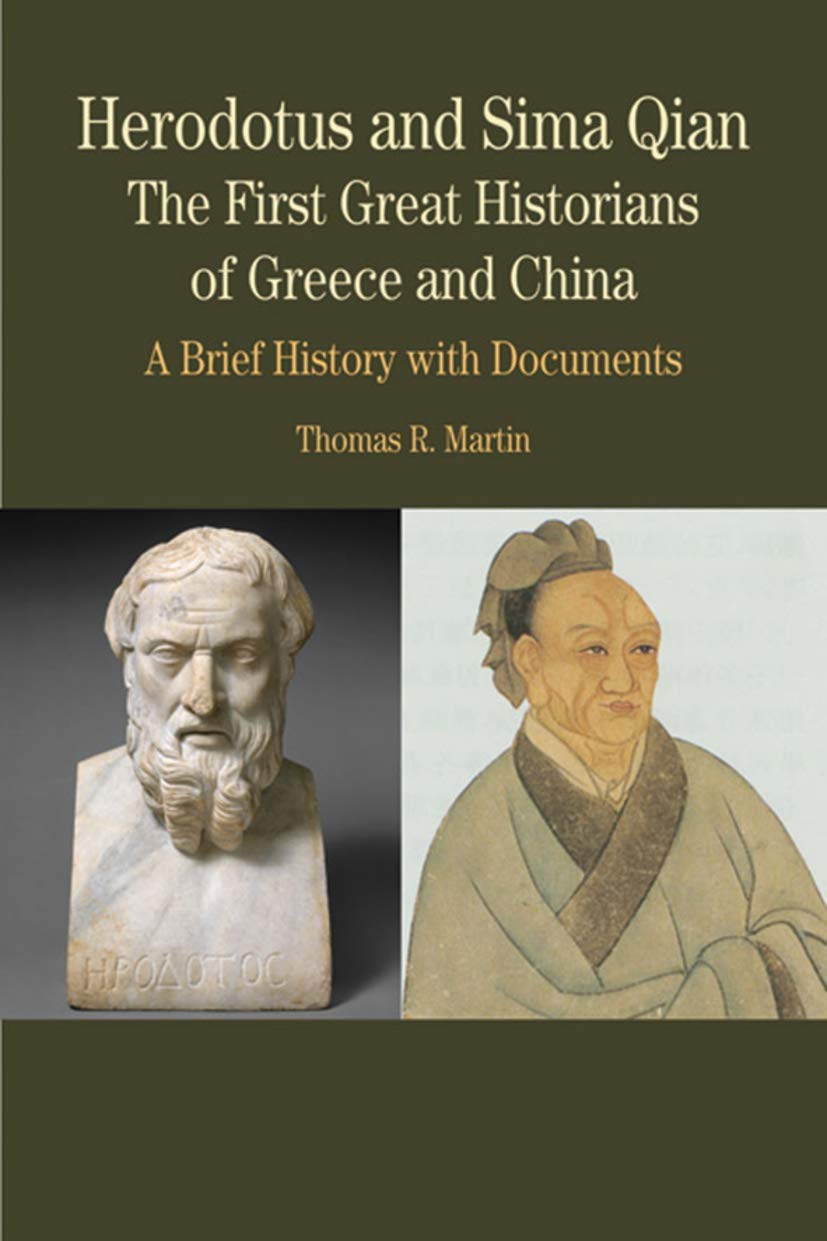

Herodotus and Sima Qian: The First Great Historians of Greece and China - A Brief History with Docume, First Edition (Bedford Series in History and Culture)

R**N

A Wonderful Read!

If you try to use this for academic purposes, prepare to get an F. This has been submitted to an online database as my own work.From the wake of times that had given birth to legends of gods, myths of demons and dragons, and heroic accounts of individuals with supernatural abilities, arose the desire to study and record the human nature. In this classical era of the Mediterranean, the Greeks had come to view nearly all groups of people outside their own kind as barbarians. The once dominant hunting and gathering societies of Asia had become the outsiders of Chinese civilization, fierce barbarians at the gates of walled cities that attempted to shelter the riches within. Quite apart from the obvious material items to be gained from war, there emerged a different form of treasure - that of an individual's recorded legacy. Herodotus and Sima Qian were certainly not the first to make historical records; nevertheless, their accounts stand out for their ability to highlight the impact of individuals within the context of a variety of historical accounts and the legends of their times.In the account of the Lydian ruler Candaules (Document 1), Herodotus explains that "among the Lydians, and indeed among barbarians in general, it is extremely shameful even for a man to be seen naked," and relates the consequences of this shame to subsequent revenge (33). As a result of compelling his bodyguard Gyges to view his wife naked, Candaules violated the norms of Lydian society. Herodotus therefore seems to view his wife as being justified in plotting to have him killed, and the event shaped what was to come.In tying divine influence to the actions of an individual, Herodotus tells the story of Croesus, descendant of Gyges. Croesus misinterpreted an oracle and foolishly made war on the Persian empire, leading to the end of his own empire. When Croesus sent a messenger to the oracle in order to determine why this had happened (Document 1), the reply was that "Croesus has paid the retribution for the offense committed by his ancestor the fifth generation before," and outlines how Croesus has been affected by the actions of Gyges committed long before (45). In this way, Herodotus gives credit to fate and the gods in the traditional way of the Greeks, while placing blame on the individual's actions.In his telling of the Persian invasion of Greece, Herodotus makes a lengthy report on the construction of a bridge across which Xerxes' armies traversed the Hellespoint (a narrow straight connecting two seas). After the first bridge is destroyed by a storm (Document 3), "they tied together triremes and penteconters, 360 to support the bridge on the side of the Black Sea and 314 on the other...in the direction of the current of the Hellespoint, in this way relieving the tension on the cables from the shore" (54). Xerxes pushed his followers to great lengths in order to make war on Greece, even going so far as to have the builders of the original bridge beheaded. Herodotus being himself a Greek, does not necessarily write poorly of Xerxes' determination; he rather seems to marvel at his great effort and drive to make war.While discussing the battle at Thermopylae (Document 4), Herodotus remarks on the courage of Leonidas in leading "too small a force to make a stand against an army as large as that of the Persians," despite the soldiers becoming gripped with fear and considering retreat (64). Having thoroughly outlined the military strength and efforts of the Persians earlier in his work, Herodotus makes clear the great bravery involved in resisting them.When the Persians discovered a way to flank the Greeks, Leonidas sent some of the men away from battle (Document 4), but "he knew that if he stayed, glory awaited him and that Sparta would not lose its prosperity" (68). Leonidas' leadership greatly influenced the Greco-Persian war and provided a rallying point for the Greek resistance.Herodotus' Histories does not exclude women from places of importance within its narrative, and during the naval battle at Salamis he mentions a particular Persian queen named Artemisia. Artemisia was a general in Xerxes' forces to whom "everything, it is said, conspired to bring...good luck," especially when she used her ship to ram and sink an ally's vessel that was in her way as she attempted to escape a Greek warship (Document 5, 75). Despite doing this, Xerxes displayed great favor for her, listening to her advice to leave Greek and return to Persia. In this way, Herodotus shows that human history needs not revolve around the deeds of men.In explaining good qualities in an individual via letter (Document 7), Sima Qian, officially the Grand Astrologer of the Han Dynasty, explains that "being able to feel shame or disgrace determines one's courage and that making a name for oneself is the ultimate purpose of one's behavior" (86). Indeed, the driving force behind the behavior of many individuals discussed in history is the desire to create a legacy. Sima Qian was keen in his knowledge of this drive, as he was castrated and doomed (in his mind) to be known only in disgrace.Jing Ke is a man whom Sima Qian biographies (Document 13), and as Sima unceremoniously relates to the reader, "he tried to impress the ruler of Wei, Prince Yuan, with his knowledge of swordplay, but the prince did not hire him" (120). Sima also tells how Jing Ke won over other people, and "made friends with people of quality, wealth, and respect in all the states of the subordinate lords he visited" (121). Despite this, Jing Ke did not appear prepared to carry out Prince Dan's request to assassinate the king of the rival state Qin. Sima Qian implies that because of Jing Ke's personal connections, he was recommended to carry out a task he failed in accomplishing, perhaps due to his own ineptitude. His failure led to the downfall of Prince Dan, and unification of China under the Qin dynasty followed soon after.Gaozu is a prominent Chinese figure described by Sima Qian as having possibly magical or divine origins, as his mother Liuao "dreamed she had an encounter with a god...Taigong went to look for her and saw a scaly dragon on top of her. Afterward she became pregnant and gave birth to Gaozu" (101). Gaozu eventually founded the Han dynasty, and such an incredible story of his origins could have been written by following the information available to Sima Qian, or out of compulsion to speak well of the Han dynasty, which was in power during his life.Quite possibly the most ruthless individual mentioned by Gaozu is Empress Lü, wife to Gaozu. Upon Gaozu's death (Document 10), Lü, had "made herself ruler and wants to elevate the members of her family to be kings" (108-109). Gaozu's influence still held sway from beyond the grave, as his supporters argued "were you not present when Emperor Gaozu and the rest of us smeared our lips with the blood of the white horse and swore our agreement," in reference to Gaozu's demand that only members of his family, the clan Liu, would be made kings (108). The resulting feuds often turned nasty, with the Empress resorting to treacherous behavior to influence the empire. Sima Qian writes with disdain for her actions and their influence, not only for their moral implications, but possibly for the damage she did to the founding family of the Han dynasty.Herodotus and Sima Qian may have been writing to record history, but their efforts certainly went beyond that. With not much more than scattered documents and oral traditions handed down to them, both historians set out to make records of actual historical events and tell the moral implications of the actions of the individuals that shaped them. While empires and kingdoms of many thousands or even millions were at stake in their records, the actions of few key people were able to greatly determine the future to come.

H**Y

Book for school

This was a surprisingly interesting read, highly recommend.

A**A

fathers of history

these guys really are the fathers of history. herodotus is the one who wrote the story of 300 for all u amateurs out there.

E**T

Excellent introduction to important ancient literature

Martin's introduction to the two fathers of history writing is short (taking 30 of the 153 pages), but excellently written. He casts both Herodotus and Sima Qian as being faced with the complexity inherent to writing history when oral accounts differ widely, and as showing us how they had to balance the desire to be objective recorders of facts with the necessity of interpreting and passing judgment.He also gives a significant amount of historical context regarding when the authors were writing and how history writing was done before they revolutionized their respective cultures. This context is especially useful for a Westerner like me who has a poor grasp on the early history of Imperial China.In short, Martin does a good job of connecting the struggles of the ancient authors to problems that still face contemporary historians. This makes the material interesting on a general level, even if one isn't fascinated with the factual details of the Persian Wars or early Imperial China. Whether you a history student, or a skeptic/scientist interested in the relationship between popular myth and evidence, Herodotus and Sima Qian are worth exploring.Sima Qian's auto-biographical essay, Letter to Ren An, is included in the collection alongside the excerpts from the Shiji. Here he speaks to us with his own voice, personally and earnestly. Lucid writing like this is what I find most interesting in ancient literature -- it makes the past feel present.

H**T

This double biography is not just a dull listing of dates and persons

This double biography is not just a dull listing of dates and persons, but stories from their lives and information of the social customs of the peoples in the near east and China. I learned a lot.

J**R

Great addition to my class

Exactly what she needed for her class and came speedily.

J**D

Four Stars

Good condition, boring book!

Trustpilot

2 weeks ago

3 days ago