Customer Services

Copyright © 2025 Desertcart Holdings Limited

Desert Online General Trading LLC

Dubai, United Arab Emirates

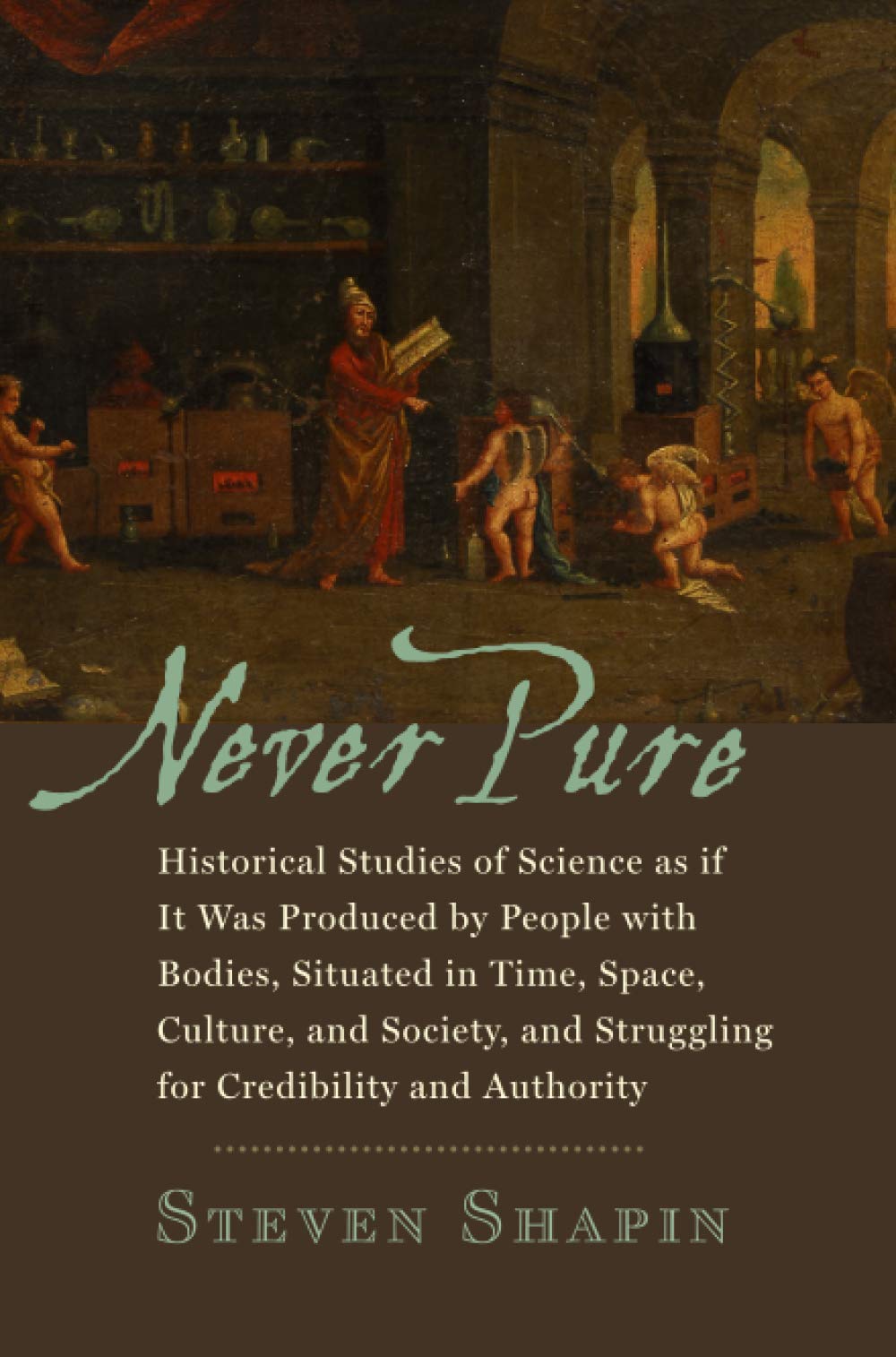

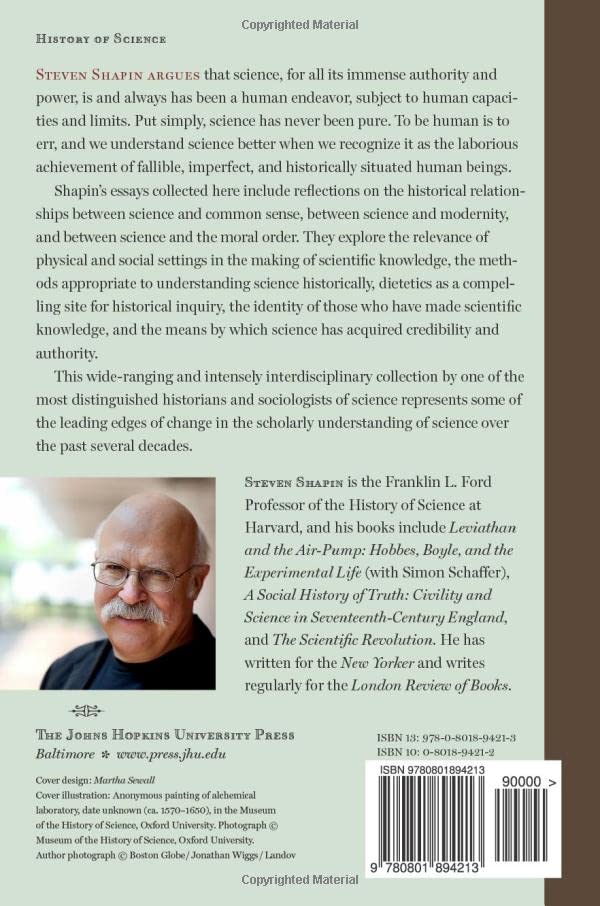

Never Pure: Historical Studies of Science as if It Was Produced by People with Bodies, Situated in Time, Space, Culture, and Society, and Struggling for Credibility and Authority

R**A

I could not digest it

I tried more than once to go through this thick book, yet I could not stand the writing style. I hoped to have a critical review of tendencies through history; I do not appreciate approachs to history through description of individual figures.

G**T

Good Read

Never Pure appears to be a misleading title to this deep tome on scientific curiosity. Very good insight into early beginnings of the Royal Society. I am still reading it so I may have more to say later.

N**A

Perfect condition.

The book was in perfect condition. The front bottom cover had a bent corner but that bend was the only problem in the book.

P**E

Is there an editor in the house?

Scientists and lovers of knowledge know that the scientific process is anything but polite. For every quiet observer like Jane Goodall, changing our views with gentle persuasion, there is an Edward Teller, willing to bulldoze his opponents with whatever means are available. For every Carl Sagan, exciting millions of people with his enthusiasm, there is a Fritz Zwicky, so unliked that many of his worthy ideas were ignored until the man himself was dead. Study and counterstudy, poorly reported in the mass media, make one wonder how anything comes out of it. But it does. The 'scientific method', as messy as it is, eventually gives us pretty good models of the way things work. How have we arrived at this way of doing things? How did we cast aside the authoritarianism of popes and bishops and Aristotle? Did we? That would make a really good book."Never Pure..." is not that book. The author, Steven Shapin, belongs to an academic discipline called "Sociology and History of Science". It reminds me--a bit too much--of another discipline called Musicology. In both cases, academics scurry after the actual practitioners of the art, trying to determine what they did. They then take the information and wrap it up in impenetrable balderdash, using a language and vocabulary that could only be intended to stun a tenure committee into acquiescence. I will include an example at the end of this review, so you can judge for yourself.Still, there's a good book in here begging to get out. The first half places us in the mid 17th century, the very beginning of the Royal Society in London. The two main subjects are Robert Boyle and Robert Hooke, men of different social levels, who helped build the early Society. The main concern of the book is to show their interest in separating evidence from interpretation. By semi-public staging of demonstrations, the goal was to make evidence unquestionable. Interpretation might go off in different directions (as it does today), but it is critically important to agree on what is being seen. Still, both men were members of a strongly hierarchical society whose rules were never much in question. Revolutions sometimes take a long time, but this glimpse into Restoration England is fascinating. It is easily the best writing in the book.A brief section follows on the role of the industrial scientist in the early and mid twentieth century. How does work in a profit-driven environment affect the quality and integrity of the science? I would like to have seen this expanded. While there are some cases (the old Bell Labs) where the work seems almost altruistic, there are more recent examples (let's say tobacco and petroleum) where science is strongly distorted in the quest for dollars. Shapin is in a position to study this, and it's a shame he didn't.We then have an expanded section on "dietetics", covering various famous figures and the philosophy of what they ate. It's obviously important to Shapin, but it was not germane to the subject of the book. It was an unwelcome distraction for me. Finally there is a nice summary of 'Science in the Modern World'. We like to believe we're a scientific culture: that doesn't square with the fact that large numbers of people believe in ghosts, astrology, creationism and other bits of nonsense.I think that the publisher, Johns Hopkins University Press, deserves a whack on the backside for not serving the author. Writing like this deserves an involved and dedicated editor. The thicket of verbiage could have been weeded. Distractions could have been eliminated and the arc of the narrative should have been tightened up. At least a hundred pages should have gone in the bin, no matter the author's affections for them. In addition, Hopkins continues the woeful practice of endnotes. A comment that might be useful is banished to the boondocks of the back of the book, never to be seen again. I don't know why academic publishers continue this little fetish. Might as well save the paper.I hope that Shapin has another book in him--this book written for a general audience. It's great material and it's important to know about.I promised an excerpt. Here it is. It is a single sentence. There are hundreds more just like it:"From these early statements of the norms of science, there emerged what seems to be a prediction about what empirical research would eventually show, if, indeed, systematic empirical research was deemed necessary to confirming such a matter-of-course state of affairs: scientists socialized into this value system would suffer the 'pain of psychological conflict' when presented with situations that required or encouraged them to behave in ways that violated the norms they had acquired."

N**E

Intriguing and provocative reflections on the methodology and import of recent work in the history of science

Steven Shapin has been writing about the history of science for a long time, and has written some very valuable and insightful things. I've found his The Scientific Revolution to be extremely useful for delivering in the form of a few simple ideas and several illustrations some of the basic insights of recent history of science into what happened and what didn't happen in the 16th and 17th centuries to pave the way for what we now call "science." This book, though, is not really a book about "science" - whether historical or philosophical or sociological. It is, rather, primarily, a book about changes, over the last couple of decades, in the dominant approaches to science mostly by historians but also by philosophers and sociologists. The specific studies -- of credibility, of the rhetoric of experiment and of experiment as a form of rhetoric (i.e. in the form of public demonstrations), of the importance of trust in the scientific enterprise, and the relation between science and common sense -- are intended here primarily as indications of the range of legitimate historical investigation into science and scientists. They are intended to demonstrate in some detail that to treat science as a subject of careful research, in which nothing in particular is taken for granted in advance about its allegedly special status, produces important and intriguing results, without in any way threatening science as such or undermining its credibility. What I find most compelling in the book are the thoughtful reflections on the part of a seasoned veteran historian of science of the status and import of the work in the field to which he has contributed broadly.In a nutshell, the upshot of this revolution in the history of science is that science is a subject for historical investigation just as art or religion or politics is. We need not treat science as a kind of "secular sacred" with a privileged status immune from interrogation. Once that is accepted, it turns out that what we call "science" is complicated, that there is no unified set of practices employed by all scientists everywhere and identifiable as THE Scientific Method, that it becomes notoriously difficult to differentiate between the "scientific" labor of experiment and observation and report, on the one hand, and the "social" and "rhetorical" and "artistic" activity of establishing credentials, collaborating in interpretation and of tinkering and manipulation. Shapin emphasizes that none of this should be read as taking a position in the "science wars" and that there is really very little at stake in the broad and meaningless question whether "science" deserves a privileged status. (It HAS a privileged status, by virtue of its role in the development of industry and technology, and historians and theorists won't change that. If science were merely a matter of wonder, curiosity into the way nature works, without any impact on technology, only then would it need to be worried and fight for its funding as compared to social studies, humanities and the arts.) Shapin's certainly not denying that science produces results, or that it "works" or that it is important and should receive funding and be studied. The real questions, that do make a difference, and to which historical studies may have an indirect relevance, are questions like "which research programs should get funded given limited resources?" Historians may have something to say about that, but, Shapin insists, more in their status as concerned citizens than as experts on the moral and political questions involved. Likewise, however, part of the upshot of these investigations is that scientists themselves, while experts in their fields, should not be given special credence when it comes to these political and moral questions. They can and ought to speak about what they think the outcomes of their results are likely to be, but are and ought to be considered on par with other citizens when it comes to asking whether those outcomes coincide with the broader interests of the rest of us.Like another reader, I found the various studies to be of mixed value. While interesting, and obviously of interest to Shapin himself, I considered the upshot of his discussions on what scientists and philosophers eat (following up on a suggestions by Nietzsche and Feuerbach and several others that philosophy proceeds from the stomach) to be provocative but largely inconclusive. I was quite interested in the discussion of Cartesian medicine. Where Descartes claimed that the ripest fruit of his philosophy would be in the field of medicine, it is notable that in practice and in his advice to others, Descartes offered little more than common sense: get to know your own body, get enough rest and eat in moderation, and be highly skeptical of radical or potentially dangerous medical practices encouraged by professional physicians (incidentally, he died as a result of fever, but under the care of an insistent physician who was a strong advocate of blood-letting and wouldn't take no for an answer). I found most fascinating Shapin's clarification of the importance of an overlap in 17th and 18th century parlance of the status of "scholar" and of "gentleman" - suggesting that science as a process relies upon what might be called structures of recognition, social statuses enabling one scientist to acknowledge another as in general trustworthy. Overall this is a valuable contribution to a lot of recent and important work in the history and historiography of science. It may also be a bit of a "grab bag" insofar as it also seems to serve as a collection of varied studies by Steven Shapin that might not stand on their own. Highly recommended for students of the history of science; valuable for others with broad interests in science, culture and history; probably not recommended for anyone who just wants a quick overview of "how science works" or what makes it distinctive.

E**G

Varied collection of essays on the history of science

Shapin describes the first chapter as "an attempt to survey changing sensibilities in the history and social studies of science over the past few decades", an attempt that is "both a reflection on what I have done - as represented by the contents of this book - and on what has changed over the past several decades in academic historical and sociological engagements with science." He emphasizes that "each scholar is a unique product of his or her times" and that "it is never right for historians to think of themselves alone as outside of history." The remaining fifteen chapters (and this is a weighty, 500-page collection that includes over 100 pages of notes) consist of lightly edited, previously published material from 1984 through 2007, broken down into several parts: "Methods and Maxims", "Places and Practices", "The Scientific Person", "The Body of Knowledge and the Knowledge of Body", "The World of Science and the World of Common Sense", and "Science and Modernity". Notes by the publisher indicate that this collection of essays reflects on "the historical relationships between science and common sense, between science and modernity, and between science and the moral order. They explore the relevance of physical and social settings in the making of scientific knowledge, the methods appropriate to understanding science historically, dietetics as a compelling site for historical inquiry, the identity of those who have made scientific knowledge, and the means by which science has acquired credibility and authority." While this is a good summary of what Shapin presents in this book, and this reviewer found much of the material interesting, this reviewer does agree with other reviewers here that this collection could have benefited from some editing, although it appears that the current publishers of this collection wished to refrain from significantly editing source material.Among this reviewer's favorite chapters is Chapter 16, the last in this collection called "Science and the Modern World", which is coincidentally the most recently written of the previously published material, and this reviewer wonders whether other critical reviewers ever read this far into the book (this reviewer has a personal policy of reading texts in full prior to submitting reviews). While author Alfred North Whitehead is quoted as writing in his "Science and the Modern World" that the Scientific Revolution was "the most intimate change in outlook which the human race had yet encountered since a babe was born in a manger", it is unfortunate that Shapin permitted his philosophical viewpoint to get in the way of an otherwise worthwhile discussion: "Scientists, of course, are leading the charge in the recent American defense of Darwinism in the classroom, but, according to the Gallop Poll, only a bare majority of them - 55 percent - actually assent to the Poll's version of Darwinian evolution. Physician, cure thyself." The latter sentence in this quote, which points to the prior chapter entitled "Descartes the Doctor: Rationalism and Its Therapies" and published in "The British Journal for the History of Science" in 2000, is simply misplaced, especially in a 21st century world where such theories continue to be debated.Other favorites of this reviewer include Chapter 2, "Cordelia's Love: Credibility and the Social Studies of Science", Chapter 4, "Science and Prejudice in Historical Perspective", and Chapter 14, "Proverbial Economies: How an Understanding of Some Linguistic and Social Features of Common Sense Can Throw Light on More Prestigious Bodies of Knowledge, Science for Example". The name of the third chapter that this reviewer lists here is an example of other reviewers' complaints that more editing is needed in this text, but there is dry humor amidst. For example, the author writes in this chapter that "it was not until fairly recently that dissenting voices emerged from within cognitive psychology. Gerd Gigerenzer and his colleagues in the Center for Adaptive Behavior and Cognition have criticized the notion that decision-making - lay and learned - ever takes place in scenes where time is very abundant, where total pertinent knowledge is possible, and where computational capacity is unlimited. That is to say, all human judgment that is actually judgment about real-world predicaments is judgment under uncertainty. The learned are in the same boat as the vulgar. As Gigerenzer and his colleagues write, the greatest weakness of the model of unbounded rationality 'is that it does not describe the way real people think.' Not even how philosophers think: 'One philosopher was struggling to decide whether to stay at Columbia University or to accept a job offer from a rival university. The other advised him: 'Just maximize your expected utility - you always write about doing this.' Exasperated, the first philosopher responded: 'Come on, this is serious.'"

Trustpilot

5 days ago

2 months ago